Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a Persian cat

Author information

Jenkins TL, Jennings RN.Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a Persian cat// J Vet Diagn Invest. 2017 Nov;29(6):900-903.

Abstract

Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) are rare causes of primary pulmonary hypertension in humans, and, in 2016, were reported in dogs. A 1-y-old, neutered male Persian cat was presented for autopsy after sudden death several hours after grooming. Grossly, the lungs were mottled red-to-pink, contained rubbery-to-firm nodular foci, and there was moderate-to-marked left-sided cardiomegaly and left atrial dilation, consistent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Microscopically, there was multifocal to regionally extensive capillary proliferation within pulmonary alveolar septa and around respiratory bronchioles, with nodular aggregates of densely arranged capillaries that replaced pulmonary alveolar spaces. Rare occlusive venous remodeling was identified in Verhoeff-van Gieson-stained sections. The gross and microscopic changes were consistent with PCH with rare features of PVOD. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was interpreted as potentially contributing to the cause of death, but unrelated to the pulmonary vascular proliferation.

KEYWORDS: Feline; cardiomyopathy; lungs; pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis

Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) are rare causes of primary pulmonary hypertension in humans, and, in 2016, were reported to occur in dogs.16 PCH is characterized by widespread proliferation of thin-walled capillaries within the pulmonary parenchyma, including alveolar septa, and bronchiolar and perivascular interstitium.6 Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease is characterized by remodeling and occlusion of pulmonary venous vasculature by fibrosis and/or recanalization.6 Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis may be a secondary change of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, and although both are reported as primary disease processes, the clinicopathologic presentation of both diseases frequently overlaps.6 The prognosis for both pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and PCH is generally poor,9 and the cause of PVOD and/or pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis in humans and dogs is unknown. In humans, proposed contributing factors include left-sided congestive heart failure, inflammation, infectious agents, and genetics.2,4,7,8,10

Elucidating the pathogeneses of these rare conditions in humans may benefit from the identification and characterization of spontaneous occurrences of PCH and/or PVOD in domestic species. We detail gross and histopathologic features consistent with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease in a domestic cat. An ~1-y-old, neutered male Persian cat was presented for postmortem assessment after sudden death ~2 h after grooming. The referring veterinarian reported that a previous medical examination several months earlier was unremarkable. On gross examination, the lungs were mottled pink-to-red, and firm-to-rubbery (Fig. 1).

Many of the red foci were firm and moderately well-demarcated on section (Fig. 1, inset). The heart weighed 24 g (0.72% body weight, reference range: 0.29–0.43%),5 and the left ventricular wall was markedly thickened (left ventricular free wall, 18 mm, reference range: 5.0–12.0 mm; right ventricular free wall, 3 mm, reference range: 1.3–3.2 mm).5 The left atrium was subjectively mildly dilated. There were no other significant gross abnormalities.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left-sided congestive heart failure was considered as a primary differential diagnosis for cause of death given the marked left-sided cardiomegaly. Tissue sections from lung, liver, kidney, spleen, heart, adrenal glands, thyroid glands, urinary bladder, pancreas, esophagus, trachea, stomach, small intestine, colon, and brain were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin.

Figure 1. Left thorax of a cat with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis.

The lungs were rubbery-to-firm, and multifocally mottled red-to-dark-red and glistening. Cardiomegaly was marked. On section, there were numerous moderately well-demarcated, dark-red foci (arrowheads, inset) throughout the parenchyma of all lung lobes.

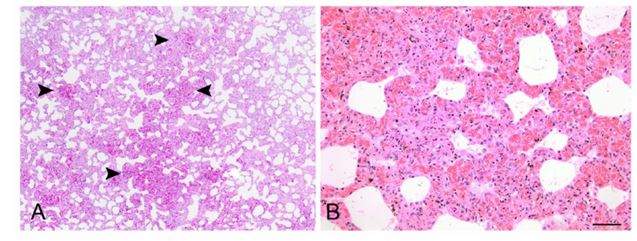

Figure 2. Lung of a cat with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis.

A. The lungs contained multifocal and coalescing regions of vascular proliferation (arrowheads) that replaced alveolar spaces. B. The vascular proliferation was composed of densely arranged, congested capillaries lined by well-differentiated endothelium. H&E. Bar = 50 µm.

The tissues were routinely processed and paraffin-embedded. Tissue sections of 5-μm thickness were cut onto slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Lung sections were also stained with Verhoeff–van Gieson (VVG) elastin histochemical stain to identify veins, noted by the presence of only a thin, external elastic lamina. Immunohistochemical labeling of endothelial cells was performed on lung sections using a mouse monoclonal anti-CD31 antibody (clone JC70A; Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA). Histologically, there was multifocal, widespread, mild-tomarked expansion of pulmonary alveolar septa by numerous, densely arranged, thin-walled congested capillaries lined by flattened, well-differentiated endothelial cells with minimal anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, affecting ~10–50% of the pulmonary parenchyma in all sections examined. The proliferating capillaries formed large expansive nodular foci, corresponding to the grossly described red, firm foci, which replaced the alveolar pulmonary parenchyma (Fig. 2).

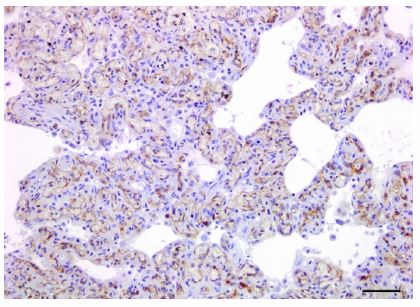

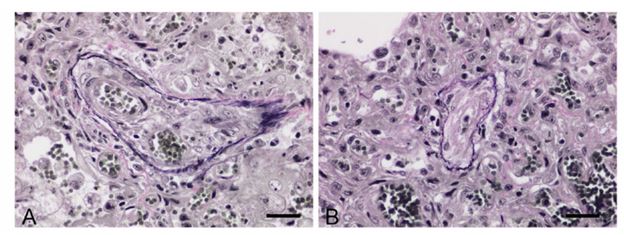

Proliferative capillaries multifocally infiltrated the interstitium along smooth muscle bundles and extended around the walls of respiratory bronchioles and small vessels. There was strong membranous CD31 labeling of endothelial cells within the proliferative thin-walled capillaries throughout alveolar septa and peribronchiolar interstitium (Fig. 3). Affected regions of lung contained focally extensive hemorrhage, fibrin, and necrosis, with accumulations of fewto-moderate numbers of hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Diffusely, there were moderate numbers of foamy macrophages within alveolar spaces (alveolar histiocytosis). Additionally, rare veins and venules, identified using VVG elastin stain, had mural remodeling and occlusion by intraluminal fibrous stroma with one to several endothelial cell–lined vascular spaces (Fig. 4), congruent with PVOD. Additional microscopic findings included left-sided ventricular cardiac myofiber disarray and mild-to-moderate multifocal interstitial myocardial fibrosis (Fig. 5).

Significant morphologic changes were not identified in the additional tissues examined. The cause of death was presumed to be multifactorial and likely the result of concurrent hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and severe primary pulmonary vasoproliferative disease, consistent with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Therefore, in the absence of a detailed clinical history, we cannot rule out that the PCH contributed significantly to the death of this cat.

Figure 3. Lung of a cat with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis.

Interstitial vasoproliferative blood-filled structures were lined by endothelial cells that have diffuse, strong membranous and cytoplasmic labeling for CD31. Immunoperoxidase–DAB, hematoxylin counterstain. Bar = 20 µm.

Figure 4. Lung of a cat with pulmonary veno-occlusive disease.

Rare pulmonary veins and venules, apparent by the presence of only an external elastic lamina, had mural remodeling with recanalization and multiple vascular lumina A. or marked luminal occlusion B. Verhoeff–van Gieson. Bar = 40 µm.

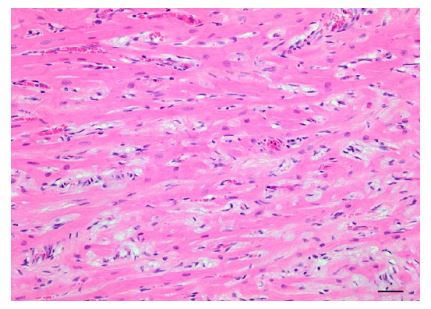

Figure 5. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cat, characterized by multifocal myofiber disarray as well as increased interstitial collagen. H&E. Bar = 50 µm.

PCH and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease are rare causes of pulmonary hypertension in humans, and are associated with a poor prognosis. In humans, pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and PVOD are diagnosed in patients ranging in age from infant to elderly. The major presenting clinical sign is dyspnea, although acute death is also reported and may be associated with right-sided heart failure, hypoxia, or respiratory failure.1,6

Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and PVOD are clinically indistinguishable, and histopathology (biopsy or autopsy) remains the definitive diagnostic test for these 2 entities.7,10 Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis were identified for the first time in a small animal domestic species in a cohort of 11 dogs in 2016.16 Affected dogs were generally older (median age: 10.5 y), and had rapidly progressive respiratory signs characterized by dyspnea, cyanosis, and pulmonary edema. Diagnosis of PVOD and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis was primarily based on histopathologic, and not clinical, features. Although PCH has not been described in large animal domestic species, regional pulmonary veno-occlusive disease has been reported and is implicated as a possible contributing factor in exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage in horses.15

In our case, the cat was ~1 y of age and reportedly showed no clinical signs prior to death. In the absence of extensive clinical investigation and given the lack of previous clinical signs, we are uncertain if this cat had overt clinical signs similar to those reported with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease in humans and dogs. The grossly described left-sided cardiomegaly and microscopically apparent cardiac myofiber disarray and fibrosis in this cat were consistent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. There are reports of concurrent hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis in humans, although the pathogenesis and relationship is unclear.

In one report, the authors proposed a pathogenesis of chronic left-sided congestive heart failure resulting in reactive pulmonary vascular proliferation.4 In another, congenital PCH was diagnosed in a stillborn fetus with concurrent HCM.11 Various pulmonary vascular changes may manifest as a result of chronic leftsided congestive heart failure (CHF) in humans.3 When severe and protracted, left-sided CHF may lead to vascular damage and vascular and interstitial remodeling, including interstitial collagen deposition, capillary proliferation, pulmonary arteriole and arterial intimal thickening, mural hypertrophy, and luminal obliteration.12,14 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a well-documented feline cardiomyopathy, yet there are no reported associations of vasoproliferative pulmonary lesions and feline HCM. Therefore, the significance and relationship of concurrent HCM and PCH in this cat is unknown. We favor interpretation of the PCH in this cat as unrelated to the concurrent HCM based on the absence of pulmonary edema indicative of prolonged pulmonary venous hypertension. Features of both pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and PCH frequently occur together in humans, and some have speculated that PCH represents an abortive angioproliferative process secondary to PVOD.6 There appears to be a similar concurrence of PCH Figure 5.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cat, characterized by multifocal myofiber disarray as well as increased interstitial collagen. H&E. Bar = 50 µm. Figure 4. Lung of a cat with pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Rare pulmonary veins and venules, apparent by the presence of only an external elastic lamina, had mural remodeling with recanalization and multiple vascular lumina A. or marked luminal occlusion B. Verhoeff–van Gieson. Bar = 40 µm. 4 Jenkins, Jennings and PVOD lesions in dogs.16 In our case, PCH was the predominant pattern in all lung sections examined, with nodular-to-widespread interstitial capillary proliferation. Rare remodeling was observed in several pulmonary veins and venules in this cat, resulting in near total obliteration of vascular lumina. These severe foci of venous remodeling are consistent with pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Alternatively, we cannot rule out that pulmonary venous hypertension and blood stasis could have resulted in venous thrombosis, leading to these obliterative veno-occlusive lesions. The rarity of lesions of PVOD suggests that the extensive pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis in this cat is unlikely to be secondary to PVOD.

These 2 disease processes were previously categorized into different groups, distinct from pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). The classification scheme was revised in 2013, with PCH and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease categorized together under the subgroup of PAH,13 perhaps representing the common concurrence of and clinicopathologic similarities of these disease processes. PVOD and PCH are considered to be extremely rare causes of PAH in humans, only accounting for ~10% of unexplained cases of PAH.13 The incidence of PVOD and PCH in veterinary species is unknown at this time. Until 2016, this was not documented to occur in domestic species, and therefore, may have been overlooked and/or misdiagnosed.

In the 2016 canine case series, 2 of the 11 cases were originally clinically misdiagnosed as chronic CHF.16 General awareness of pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease within the veterinary community is imperative to better diagnose, ascertain incidence and pathogenesis, and potentially direct treatment of these rare diseases. The identification of PCH and PVOD in multiple domestic species may lead to valuable comparative models for PCH and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Acknowledgments We thank Dr. Kurt Williams for his consultation with histopathology, and to Florinda Jaynes for her expertise in performing the immunohistochemistry. Declaration of conflicting interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Almagro P, et al. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis associated with primary pulmonary hypertension. Medicine 2002;81:417–424.

- Eyries M, et al. EIF2AK4 mutations cause pulmonary venoocclusive disease, a recessive form of pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet 2014;46:65–69.

- Georgiopoulou V, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction with pulmonary hypertension, Part 1: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and definitions. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:344–354.

- Jing X, et al. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: a unique feature of congestive vasculopathy associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998;122:94– 96.

- Kershaw O, et al. Diagnostic value of morphometry in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Comp Pathol 2012;147:73– 83.

- Lantuéjoul S, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:850–857.

- Mandel J, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1964–1973.

- Moritani S, et al. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis incidentally detected in a lobectomy specimen for a metastatic colon cancer. Pathol Int 2006;56:350–357.

- Ogawa A, et al. Safety and efficacy of epoprostenol therapy in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Circ J 2012;76:1729–1736.

- O’Keefe MC, Post MD. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: a rare cause of pulmonary hypertension. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139:274–277.

- Oviedo A, et al. Congenital pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol 2003;36:253–256.

- Pietra G, et al. Pathologic assessment of vasculopathies in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43(Suppl S):S25–S32.

- Simonneau G, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;42(Suppl 25):D45– D54.

- Tudor R, et al. Pathology of pulmonary hypertension. Clin Chest Med 2013;34:639–650.

- Williams K, et al. Regional pulmonary veno-occlusion: a newly identified lesion of equine exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage. Vet Pathol 2008;45:316–326.

- Williams K, et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: a newly recognized cause of severe pulmonary hypertension in dogs. Vet Pathol 2016;53:813–822.

- Assessment of longitudinal systolic function using tissue motion annular displacement in healthy dogs

- An update on canine cardiomyopathies - is it all in the genes?

- Echocardiographic identification of atrial-related structures and vessels in horses validated by computed tomography of casted hearts

- Malignant mesothelium as a diagnostic aid in canine pericardial disease

- Canine idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Part II: pathophysiology and therapy

- Effects of pimobendan on myocardial perfusion and pulmonary transit time in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease: a pilot study

- Cranial vena caval syndrome secondary to transvenous pacemaker implantation in two dogs

- Mitral valve repair in dogs

- Oculocardiac reflex induced by zygomatic arch fracture in a crossbreed dog

- The evolution of the natriuretic peptides - Current applications in human and animal medicine

- Thoracoscopic pericardiotomy as a palliative treatment in a cow with pericardial lymphoma

^Наверх