Clinical and echocardiographic findings in an 8 year old Brown Swiss cow with myocardial abscess

Author information

Gerspach C., Schwarzwald C.C., Hilbe M., Buczinski S. Clinical and echocardiographic findings in an 8 year old Brown Swiss cow with myocardial abscess // J Vet Cardiol. 2016 Jun;18(2):194-8.

Abstract

Intramyocardial abscesses are rare in cattle and may lead to unspecific clinical signs. This case report describes the clinical and echocardiographic findings in an 8 year old Brown Swiss cow presented with an intramural myocardial abscess. The main clinical findings were anorexia, drop in milk yield, fever, tachycardia, and hyperfibrinogenemia. Neither heart murmurs nor cardiac arrhythmias were present on auscultation. Transthoracic echocardiographic examination revealed a prominent intramural mass embedded in the left ventricular free wall and bulging into the lumen of the left ventricle. Diagnosis was confirmed at necropsy. A culture of the abscess grew Trueperella pyogenes.

KEYWORDS: Cattle; Endocarditis; Heart disease; Trueperella pyogenes

Abbreviation

LV left ventricle

An 8 year old Brown Swiss cow was presented to the hospital with a 1-day history of anorexia and drop in milk yield. The cow was part of a dairy herd with 65 milking cows, fed with a total mixed ration containing grass silage. The cow was 275 days in milk and 10 weeks pregnant. The cow was referred without any treatment. On presentation the cow was depressed but responsive. The cow was in poor body condition, stood with its elbows abducted and was grinding its teeth. The cow was grade 3.5/ 5 lame in its left hind limb. The rectal temperature was 38.1 °C (reference interval 38.5—39.0 °C) and the ears were cool on palpation. The heart rate was moderately increased at 92 beats per minute (reference interval 60—80 beats per minute) and the respiratory rate was normal at 28 breaths per minute (reference interval 20—35 breath per minute). The mucous membranes were slightly pale and the capillary refill time was 3 seconds. Based on eye ball recession and skin tent, the cow was slightly dehydrated (5—7%). The jugular veins were not distended. Thoracic and cardiac auscultation revealed no abnormalities. Rumen motility was reduced, with 1 contraction per 2 minutes and there was a reduced amount of ruminal content. The withers’ pinch test, the xiphoid pressure test and deep palpation with the closed fist of the cranio-ventral abdomen did not reveal evidence of pain. The glutaraldehyde test revealed clot formation at 3.5 min (normal 10—15 min), indicating elevated blood fibrinogen and/or globulin concentration. The rectal examination was unremarkable and the feces had a moderate amount of undigested fiber.

Further diagnostic work up included initially a complete blood cell count, a chemistry panel and an ultrasonographic examination of the thorax and abdomen. Radiographs of the reticulum were also taken. Hematologic analysis revealed a normal leukocyte count with 8.2 x 109/L (reference interval 4.0—8.8 x 109/L), but increased total protein concentration (97 g/L, reference interval 63—86 g/L) and hyperfibrinogenemia (9 g/L, reference interval 5—7 g/L). Ultrasonography of the thorax and abdomen revealed no abnormalities and on radiographs the reticulum was normal in shape and position. There was no evidence of a metal opaque foreign body or a magnet.

Examination of claws of both hind limbs revealed heel erosions, deformation and deep horizontal fissures suggestive of chronic laminitis, and sole ulcers on the lateral claws. After therapeutic claw trimming under local anesthesia,e a silicon blockf was placed under the left medial claw, bandages were applied and the cow was placed in a straw bedded stall. The cow then received 10 L of 0.9% saline with 5% glucose administered intravenously and ketoprofen,8 3 mg/kg, intravenous, daily.

On the day after presentation, the cow developed more severe tachycardia with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute and its rectal temperature had increased to 39.6 °C. Because of suspected infection and persistent tachycardia, transthoracic echocardiography was performed to detect possible bacterial endocarditis.

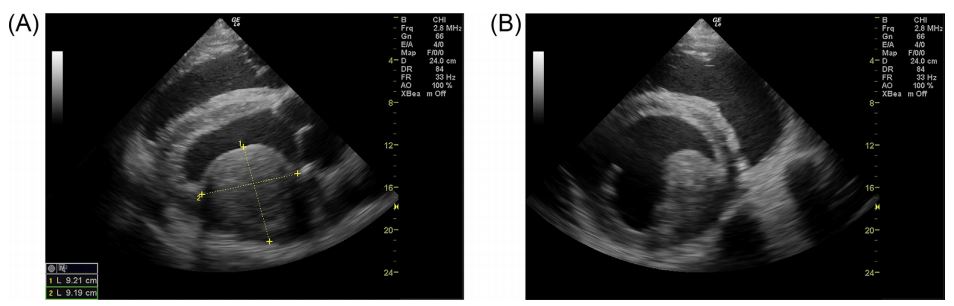

Echocardiographyh was performed from the right parasternal window using a 2.8 MHz phased- array probe.* i The cardiac valves appeared to be normal. On the right parasternal long axis view of the left ventricular outflow tract, a 9.2 cm x 9.2 cm circular, non-pendunculated mass was observed embedded in the free wall and bulging into the lumen of the left ventricle (LV). It did not appear to be associated with the mitral and aortic valves. The mass had a slight heterogeneous appearance and its echogenicity was comparable to other parts of the myocardium (Fig. 1A). The right parasternal short axis view at the level of the papillary muscles and the chordae tendineae showed that the mass was in close relation and not distinguishable from the anterior papillary muscle of the mitral valve (Fig. 1B and Online Video 1). The appearance of the myocardial mass in association with fever, hyperfibrinogenemia and shortened glutaraldehyde test suggested that the mass was an intramural abscess. The most important differential diagnosis was myocardial neoplasia. Owing to the poor prognosis the cow was euthanized.

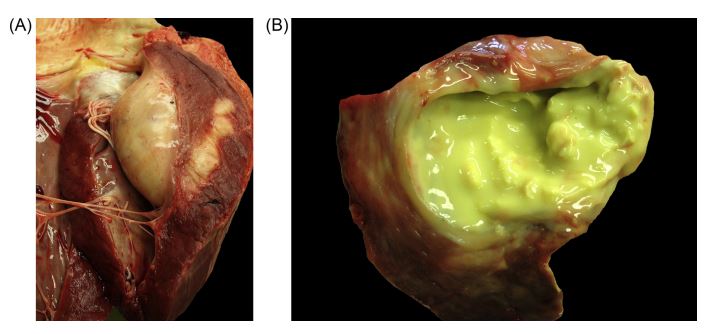

A complete necropsy was performed. After opening the heart, a round, solid-elastic, yellowish, 8 cm x 9 cm mass, was identified in the free wall of the LV, 3 cm below the mitral annulus (Fig. 2A). From the mass, approximately 50 mL of yellow-green, creamy and friable fluid could be drained. The cut surface revealed a firm, elastic capsule (Fig. 2B). The surface of the mitral valve was rough, with a granular structure. Histo- pathology revealed moderate endocarditis of the mitral valve. All other internal organs were normal. A culture of the abscess grew Trueperella pyogenes. There were no further abnormal intrathoracic findings.

Fig. 1 Intramural myocardial mass displayed in a right parasternal long axis (A) and short axis (B) view

The mass is located in the region of the anterior papillary muscle of the mitral valve.

Based on the findings, a diagnosis of myocardial abscess and endocarditis was established.

Discussion

Myocardial abscess is a rare but serious cardiac condition in people and domestic animals. Myocardial diseases in cattle usually include cardiomyopathy and myocarditis caused by viral, bacterial, or parasitic infection [1]. Deficiency of vitamin E, selenium or copper can lead to nutritional cardiomyopathy [1]. Toxic cardiomyopathy is reported secondary to ionophore toxicosis. The myocardium can also be affected in cattle with lymphoma [2].

While endocarditis is common, myocardial abscesses are uncommon in dairy cattle. Myocarditis and myocardial abscesses, associated with Histophilus somni, have been described as a cause of sudden death in feedlot calves and are classically located in the papillary muscles of the LV [3]. Other cases of myocardial abscesses have also been described but the echocardiographic findings have not been fully described. One septal abscess was found in a cow at slaughter and one abscess in the free wall of the LV on echocardiography in a calf with tetralogy of Fallot [4,5]. Gavaghan et al [6]. reported an abscess at the apex in an adult cow diagnosed with Eisenmenger’s complex and multiple abscesses in the body.

Fig. 2 Gross pathology images of the heart from a cow with myocardial abscess

(A) Round, solid-elastic, yellowish mass 3 cm below the mitral annulus was identified in the free wall of the left ventricle. (B) Yellow-green, creamy and friable fluid draining from the mass.

In people, myocardial abscesses most often develop following infective endocarditis, but also in association with sepsis, myocardial infarction, heart surgery, implant placement, and hemodialysis [7]. The most common location of myocardial abscesses is the LV, followed by valve ring abscesses, septal, right ventricle, and atrial abscesses [7,8]. They can be solitary or multiple. Depending on size and location they can be clinically silent and only be found at necropsy. Fatal sequelae of myocardial abscesses are myocardial ruptures, causing communication between ventricles or perforation into the pericardium [9,10]. Furthermore, myocardial abscesses can trigger various cardiac arrhythmias. Organisms identified in people associated with myocardial abscesses, in descending order of frequency, are Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides, Escherichia coli, beta- hemolytic Streptococci and Streptococcus pneumoniae [8]. In single cases Klebsiella, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae have been reported [11—13]. Also fungal abscesses can develop, including Aspergillus spp [14]. and Candida albicans [15].

In this case, the primary complaint for referral was not related to signs of heart failure. With reduced milk production and tachycardia, the cow exhibited clinical signs which are rather unspecific in cattle. Based on the initial examination, in absence of overt clinical signs of heart disease or heart failure such as heart murmurs, rhythm disturbances, dyspnea, tachypnea, cough, cyanosis, peripheral or pulmonary edema, distended jugular veins, jugular pulse and syncope, heart disease was not suspected initially. However, because of suspected infection and persistent tachycardia, cardiac disease became an important differential diagnosis even in the absence of cardiac murmurs or arrhythmias. Tachycardia is a common finding in compensated cardiac disease and congestive heart failure and occurs in cattle with bacterial endocarditis, traumatic pericarditis, and congenital cardiac defects [16—19]. Buczinski [2] also reported tachycardia as a consistent finding in seven cows with cardiac lymphoma. Persistent tachycardia in association with fever should prompt an echo- cardiographic examination.

In the present case, myocardial abscess or neoplasia could not be differentiated based on echocardiography because of the relatively homogenous appearance of the mass. In the light of hyperfibrinogenemia, a shortened gluta- raldehyde test, fever, and hyperproteinemia, an abscess was considered more likely than neoplasia. On necropsy, a culture of the abscess grew Trueperella pyogenes (former Arcanobacterium pyogenes), which is the most common agent in bovine bacterial endocarditis [20], followed by Streptococcus ssp., Staphylococcus spp., Pas- teurella spp., and Corynebacterium spp [21]. Recently, Helcococcus ovis was reported as emerging pathogen in bovine bacterial endocarditis [20]. Also E. rhusiopathiae has been reported in bovine endocarditis [22]. The source of bacterial spread within the blood stream is usually a chronic infection at some distant side. Lameness has been reported in association with bacterial endocarditis, with a sensitivity and specificity of 43.5% and 95.3% [18,19]. In the present case, the cow had multiple pathologic conditions of the claws, which could have been the source for bacteremia.

It is unclear what prompted the formation of an abscess in the myocardium, but the location in the papillary muscle of the LV corresponded to the classically reported lesions [3]. Abscess formation could have been secondary to endocarditis. However, echocardiography did not reveal clear evidence of valvular endocarditis and although endocarditis of the mitral valve was found on histopathologic examination, no evidence of bacteria was present. Other factors that could have triggered primary bacterial infection of the myocardium, including focal ischemia and necrosis of the papillary muscle. However, in this case this remains pure speculation. In summary, a myocardial abscess can lead to persistent tachycardia. Transthoracic echocardiography allows detection and more specific assessment of the size and position of myocardial abscesses. However, its ultrasonographic appearance may not be specifically distinguishable from a neoplasia, and other clinical and laboratory findings may need to be considered for an ante mortem diagnosis.

Conflict of interest statement

Colin C. Schwarzwald is a member of the review board of the Journal of Veterinary Cardiology.

None of the other authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Buczinski S, Rezakhani A, Boerboom D. Heart disease in cattle: diagnosis, therapeutic approaches and prognosis. Vet J 2010;184:258-263.

- Buczinski S. Echocardiographic findings and clinical signs in dairy cows with primary cardiac lymphoma: 7 cases (2007-2010). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;241:1083-1087.

- O'Toole D, Allen T, Hunter R, Corbeil LB. Diagnostic exercise: myocarditis due to Histophilus somni in feedlot and backgrounded cattle. Vet Pathol 2009;46:1015-1017.

- Sturm F. Abscess in the heart septum of a cow. Necropsy findings. Tieraerztl Prax 1985;13:297-298.

- Reef VB, Hattel AL. Echocardiographic detection of tetralogy of Fallot and myocardial abscesses in a calf. Cornell Vet 1984;74:81-95.

- Gavaghan BJ, Kittleson MD, Decock HEV. Eisenmenger's complex in a Holstein-Friesian cow. Aust Vet J 2001;79: 37-40.

- Khan B, Strate RW, Hellman R. Myocardial abscess and fatal cardiac arrhythmia in a hemodialysis patient with an arterio-venous fistula infection. Semin Dial 2007;20(5): 452-454.

- Chakrabarti J. Diagnostic evaluation of myocardial abscesses. A new look at an old problem. Int J Cardiol 1995;52:189-196.

- Lange E, Beaudu-Lange C. Septal myocardial abscess in a male great Anglo-French hound. J Small Anim Pract 2009; 50:311-316.

- Anguera I, Quaglio G, Ferrer B, Nicolas JM, Pare C, Marco F, Miro JM. Sudden death in Staphylococcus aureus-associated infective endocarditis due to perforation of a free-wall myocardial abscess. Scand J Infect Dis 2001;33:622-625.

- Abdul-Waheed M, Yousuf MA, Schneeberger EW, Naz T, Eckert DC, Conway G, Helmy T. A rare case of Klebsiella pneumoniae myocardial abscess. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:34-35.

- Al Soub H, Al Maslamani M, Al Khuwaiter J, El Deeb Y, Abu Khattab M. Myocardial abscess and bacteremia complicating Mycobacterium fortuitum pacemaker infection: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:1032-1034.

- Nandish S, Khardori N. Valvular and myocardial abscesses due to Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29:1351-1352.

- Kim HW, Moon MH, Lee JW. Myocardial abscess, a rare form of cardiac aspergillosis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 107:415-417.

- Bhatti MA, Karmarkar R, Wagner DK. Candida albicans myocardial abscess. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2003;13: 456-458.

- Buczinski S, Francoz D, Fecteau G, Difruscia R. A study of heart diseases without clinical signs of heart failure in 47 cattle. Can Vet J 2010;51:1239-1246.

- Buczinski S, Francoz D, Fecteau G, DiFruscia R. Heart disease in cattle with clinical signs of heart failure: 59 cases. Can Vet J 2010;51:1123-1129.

- Buczinski S, Tsuka T, Tharwat M. The diagnostic criteria used in bovine bacterial endocarditis: a meta-analysis of 460 published cases from 1973 to 2011. Vet J 2012;193: 349-357.

- Mohamed T, Buczinski S. Clinicopathological findings and echocardiographic prediction of the localisation of bovine endocarditis. Vet Rec 2011;169(7):180.

- Kutzer P, Schulze C, Engelhardt A, Wieler LH, Nordhoff M. Helcococcus ovis, an emerging pathogen in bovine valvular endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:3291-3295.

- Post KW, Rushton SD, Billington SJ. Valvular endocarditis associated with Helcococcus ovis infection in a bovine. J Vet Diagn Invest 2003;15:473-475.

- Edwards GT, Schock A, Smith L. Endocarditis in a British heifer due to Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae infection. Vet Rec 2009;165:28-29.

^Наверх